The Huguenot Colony at Portarlington, in the Queen's County.

(Continued.)

by Sir Erasmus D. Borrowes, Bart.

"It is certain that though there was at first a very great number of Protestants condemned to the gallies, the bastinado and other torments have destroyed above three-fourths of them, and the most of those who are still alive are in dungeons; as Messieurs Beausillon, De Seres, and Sabatier, who are confined in the dungeon at Chateau D'If (a fort built on a rock in the sea, three miles from Marseilles,) but the generous constancy of this last, about eight or ten months ago, deserves a place in history, and challenges the admiration of all true Protestants. Monsieur Sabatier, whose charity and zeal equals that of the primitive Christians, having a little money, distributed it to his brethren and fellow-sufferers in the gallies; but the Protestants being watched more narrowly than the rest, he could not do it so secretly; he was discovered, and brought before Monsieur De Monmort, Intendant of the gallies at Marseilles; being asked, he did not deny the fact. Monsr Monmort, not only promised him his pardon but a reward, if he would declare who it was that had given him that money. Monsieur Sabatier modestly answered, that he should be guilty of ingratitude before God and man, if by any confession he should bring them into trouble who had been so charitable to him; that his person was at his disposal, but he desired to be excused, as to the secret expected from him. The Intendant replied, he had a way to make him tell, and that immediately; he then sent for some Turks, who at his command stript Sabatier perfectly naked, and beat him with the ends of ropes and with cudgels for three days, at several times; and, seeing this did not prevail over this generous confessor, he himself (which never happened to an Intendant before) turned executioner, striking him with his cane, and exclaiming to the bystanders, 'see what a devil of a religion this is.' These were his own expressions, as is credibly reported by persons, and indeed the gazettes and public letters gave us the same account. At last, seeing he was ready to expire, he commanded him into a dungeon, where, in spite of all torments, Providence has preserved him to this day." Monsr Sabatier was living in 1707. A member of the family, and a worthy magistrate of a county, still resides not many miles from the original refuge. We were forcibly struck by a happy and appropriate application of the motto of the Sabatiers, "Toujours prêt.":-- from Scotland's illustrious bard we learn that James V. of Scotland graced the shield of Sir John Scott, of Thirlestane, with proud armorial distinctions

"For faith 'mid feudal jars;

What time, save Thirlestane alone,

Of Scotland's stubborn barons none

Would march to Southern wars;

And hence in fair remembrance worn

Yon sheaf of spears his crest has borne;

Hence his high motto stands revealed

"Ready, aye ready," for the field."

The gallant knight, with devoted loyalty, was ever ready at his monarch's call to marshal his forces in the field under the bannered lion of Scotland, and he reaped an earthly reward. But Francois Sabatier armed with the sword of the spirit, and the shield of faith, was ever ready "in stripes, in imprisonments, in tumults," with an unshaken constancy and a courage unsubdued, to strive under the banner of the gospel in the noble army of martyrs for a higher inheritance, which, unlike earthly honors, fadeth not away.

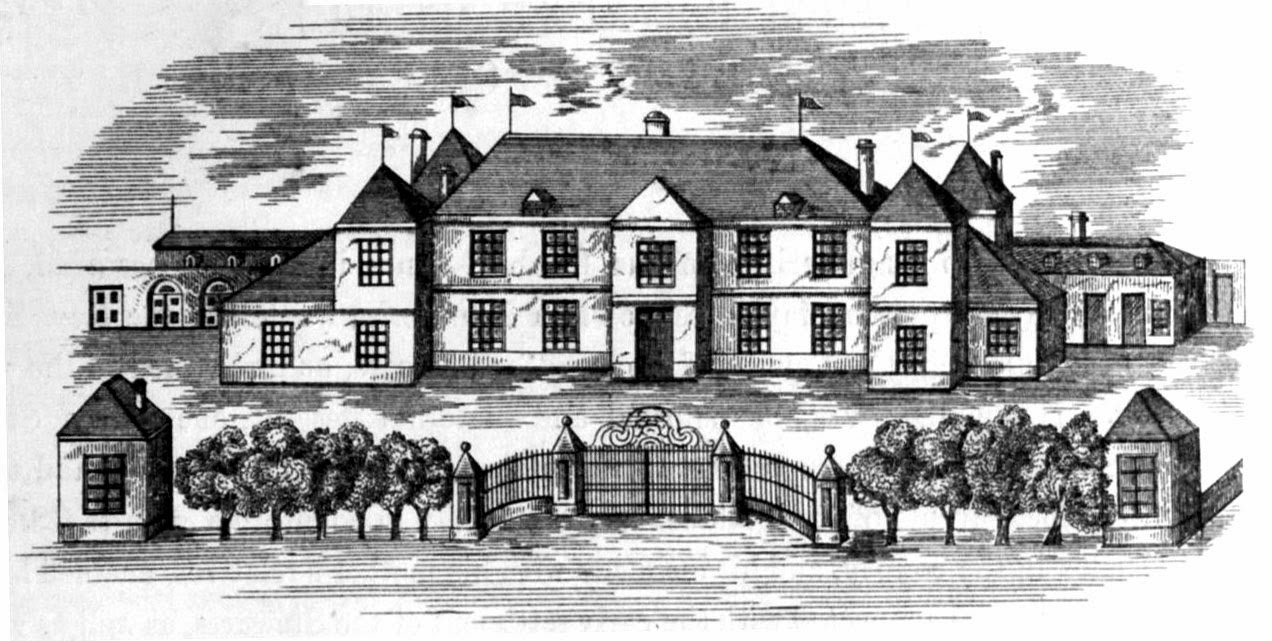

Among the earliest and chief colonists of Portarlington were Henri Robert D'Ully, Vicomte de Laval, his wife Magdeleine de Schelandre, Vicomtesse de Laval, and their family. This nobleman claimed descent from Henri Quatre; and when the storm of persecution which desolated France overtook him, he was residing on his estates at his chateau of Gourlencour, in Picardie, in honour and independence. The engraving which accompanies the present article is taken from a drawing of the Chateau, in the possession of Mrs. Willis of Portarlington, great grand-daughter of the Vicomte: it represents the handsome and picturesque residence of a French nobleman in all its national features, as it existed in the 17th century. From this residence he was hurried away in August, 1688, and cast into the dungeons of Verneuil. The cruelty of dispersing families, then too common, and confining the different members in separate prisons, was deeply inflicted on the circle of this nobleman. The Vicomtesse was shut up in the prison of Sedan, while her eldest son, a mere youth, who had been placed under the care of a kind aunt who admirably fulfilled her trust, was incarcerated in the dungeons of Laon, from which he was not liberated until March, 1705, having been separated at least ten years from his parents, who were settled in Portarlington so early as 1695. Immediately after his liberation by order of the Intendant, he addressed a most affectionate letter to his father, dated "Fontaine, 4 March, 1705," assuring both parents of his love "quoique cependant j'en ay été privée dès ma plus tendre jeunesse, la nature pourtant m'a assez fait concevoir la douleur que les enfans recoivent d'être auprès d'un père et d'une mère aussi bon et aussi charitable que vous l'êtes envers mes chères frères et soeurs." This kind father and mother had a large family of sons and daughters, two of whom were born in the prisons of France. Of the former no less than five were in the army in Queen Anne's reign, and these afflicted parents, in addition to the calamities entailed on them as the common lot of the noble refugees, (and these seem to have been in their case many and excessive,) had yet to endure the deeper and more grievous affliction of losing on the field of battle three of their youthful and gallant sons.

"Thou canst not name one tender tie

But here dissolved its reliques lie!

And now behold the mourner's veil

Shrouds her thin form and visage pale:

Or see, how manlier grief suppress'd

Is labouring in a father's breast."

The following letter was written to his sister by Louis Fontaine, a younger son of the Vicomte deLaval, called "Fontaine" from his father's estate of that name in Picardy. Three of his sons were present in the action referred to, in which one was killed:--

"May 26, 1709. .

"Living at Mademoiselle De Grange's, at Dinan in Bretagne.

"My dear Sister, -- Since I saw you last I have endured great hardships. Having sailed for two days after our embarkation at Cork, on the third day we encountered a large man-of-war with 50 guns and a mortar, and although we had but 36 cannons we fought the French for some time, until we lost a considerable number of men, and among the killed was my poor brother Joseph: he was shot with a cannon ball, and poor Mons. De Beltem with a great many more besides. And when the French boarded us, they took from us all we had, and brought us into their own ship, and put the officers and us into a large room where we lay on deck for three or four nights before we came to land. They disembarked us at Brest, where we remained two days; and while we were there Captain Nicolan gave Davido and me an English half-crown, and bid us to be as economical as possible, as he had only two for himself and his son, and we were allowed by the King only fivepence a day. They then sent us from Brest to Dinan, which is forty leagues distant; we performed most of the journey on foot; every league is three long miles. We were five days and a half on the journey, and David and I have walked 21 miles in a day. Had it not been for some gentlemen that were with us, we should never have been able to make the journey, for our officer was not with us, and did not know we were gone until after our departure. When we arrived at Dinan they put us into the castle, and there we lay on the ground on straw. Then next day they allowed us to go into the town, where they gave us a lodging for fourpence a night, and agreed to dress our food. Excuse me to my father and mother, for I was unwilling to inform them of this bad news, and pray, dear sister, give my brother's and my duty to my father and mother, and assure them that we are both well, and wish to be with them; and give our regards to my sisters, and to all who enquire for us, whom it would be too long to name.

"Your loving brother till death,

"LOUIS FONTAINE."

Among several interesting relics yet remaining in the possession of the lady already referred to as the descendant of the Vicomte, is a long and interesting address from that nobleman to his children whose escape had been effected, dated "De Guize, le 2 Avril, 1689," being then imprisoned there. In the commencement he tells them his letter will inform them of his miserable condition; he alludes to "the wretched imprisonment" of their cousins De Lussi in a convent at Soissons. The captive father then proceeds affectionately to address his youthful family, in a strain of morality and evincing that comprehensive knowledge of Scripture and readiness in controversy by which the refugees of the gentilitial classes were so remarkably distinguished; the fruits of the superior education acquired at the excellent schools established in such numbers by the Huguenots at La Rochelle and elsewhere throughout France, and the revival of which imparted such academic fame to their future settlements, and signally distinguished in this respect the town of Portarlington. This letter of the Vicomte also shows that his mind was deeply imbued with a spirit truly Christian. Passing from this the writer proceeds thus to describe to his children the prison-life of their parents, the trying scenes they had passed through, and the miseries they had experienced, the most distressing of which appears to have been the barbarous and unmanly cruelty of holding the Vicomtesse a prisoner on two interesting occasions. He then proceeds as follows:--

"My dear children, as I spoke to you at the commencement of this letter of my captivity, I told you that it continued still with great inconveniences, really insupportable, to the extent that I had lost all hope of ever seeing you again, of which my persecutors wished to convince me, unless I made you return, assuring me that this was the only means to restore me to liberty; but God was merciful to me (notwithstanding the torments they inflicted on me) to enable me to refuse them a condition so cruel and prejudicial to your eternal salvation. You were too happy in leaving such a sink of vice that I should consent by a cowardice unworthy of the name and profession of a Christian, and of a Christian enlightened by the divine mercy through the Holy Gospel, to plunge you into it again. You know that I was arrested by the police of Soissons, the 17th of the month of August, and conducted into the prisons of Verneuil, and this was for being accused, as was formerly St. Paul, for the hope of Israel; that is to say, for holding the name of God in the purity and the simplicity that it pleased him to reveal to us in his word, a crime which they esteem at present in France the most fearful, and that they visit with punishment the most severe; this was the reason that I was so strictly guarded in a place most disagreeable and inconvenient, and in which I was nearly smothered by different kinds of animals, and where there was not even room to arrange a bed. I was not there long before I fell ill; it was there that I beheld myself abandoned by all the world; I heard from my friends, for it was not permitted to them to see me: but those who presented themselves for the purpose of annoying me had all license for doing so, and of such people there were only too many to be found. Even your poor mother saw me but rarely, and with the greatest difficulty, which obliged her, though very inconvenient from the approach of her accouchement, to make a journey to Soissons, to try and obtain from our Intendant the favour to be allowed to take care of me in my illness, and to afford me some kind of liberty, fearing that I could not survive any length of time in so miserable a place, and even offering herself to remain in prison in my place for some time; but they were inexorable to her prayers, and she returned without having obtained anything. You can imagine what was her sorrow and grief: however, the good God who always paternally chastises his children, and who never strikes them with one hand that he does not raise them up with the other, bestowed on me the strength and vigour to vanquish that illness notwithstanding the hardships I had to bear. Thus, at the end of 12 days I found myself a little better, which made her resolve to take a secret journey into her country, to receive some arrears that her father-in-law owed us, the term of payment being past; and this is what has been partly the cause of all my sufferings, and that we have so long deferred following you: for as he wished for nothing so much as that some obstacle should present itself to prevent him from paying this money, he judged the authority which I had given to your mother to receive that sum, because it had been drawn up in the prison, was not sufficient, and that a man in the situation in which I was, could not legally negotiate or authorise it; which obliged her thus to make a useless journey; and, to fill the measure of her misfortunes, she found on her return that they had transferred me from the prisons of Verneuil to those of Guise, They thought it was not yet bad enough there. To effect this the police of Laon had orders to come and remove me on the 27th of Sept., and to conduct me to Guise. I was not quite recovered from illness; however, I had to travel, and they tied me with many cords on a horse. The officer who commanded the escort, an upright man, and who had formerly conducted me to the prison of Sedan, for the same cause of my religion, observed that he was touched with my condition, and assured me that they only transferred me that I might be better; but I well experienced to the contrary. He excused himself for the cruel and inhuman manner in which they treated me, making me understand how express his orders were, and to what extent he was forced to obey them; and as to me he esteemed me too happy in suffering for the profession of the truth. All the population of the town came out into the streets to see me; it was not that they had not seen me many times in a similar condition, but not tied and bound with cords, as I now was. I was visited by many melancholy thoughts during the journey, but never had anything so much afflicted me as on arriving at Guise to see a mob excited against me (who could do me no evil because they were prevented) and heaping on me a thousand atrocious insults. I remembered that the Saviour of the world replied not to such outrages, and I had the honour to imitate him in that respect; nevertheless this heart, little regenerated, was with difficulty prevented from showing its resentment. How often did I ardently ask of God to support me patiently under this insult; and then the words of the prophet David, in Psalm 69, came to my mind, where he says, -- "For they persecute him whom thou has smitten; and they talk, to the grief of those whom thou hast wounded." This passage of Scripture for a long time occupied my thoughts, finding that it exactly suited my case. They lodged me in the most frightful part of the tower, so far removed from the business of the world that I neither saw nor heard any thing but the gaoler, who came a moment each day to see what I was doing. I was two days and two nights without knowing if I was dead or alive, and consequently without dreaming of taking any nourishment: so much was I penetrated with grief and agony, and so extraordinary was my depression, that I could not even address God, nor invoke him but by interrupted and unconnected prayers; the end of the 70th Psalm was continually on my lips, saying with the author -- "But I am poor and needy; make haste to me, Oh God! Thou art my help, my deliverer; Oh Lord! make no tarrying." Reflecting upon these words I pictured to myself, that my trials were similar to those of the Prophet when he pronounced them, which gave me Borne consolation; but when I reflected that instead of lodging me better than when at Verneuil -- as the officer who conducted me made me hope -- on the contrary, they treated me with such rigour and inhumanity, it came into my head that they wished to make me serve as an example in the province, aud the image of death continually presented itself before me, which made me exclaim with the same Prophet, as in the 77th Psalm. It was from what I said in that hour that God came to my assistance, or I should have died.

It was then I knew my weakness, and how little I was disposed to be a martyr, and on this subject I earnestly implored divine assistance to aid me, entreating that He would be pleased to accord me strength and courage to do nothing unworthy of the profession of a reformed Christian, of which I had the honour to experience the light; but God had not reserved for me a part so glorious as to seal His truth with my blood; of which I became aware in seven or eight days after, by the arrival of the Intendant at Guise, who I knew was favourable to me. However, your mother, the day after her return to Verneuil, set out again to see me, and God willed that her journey was so apropos that she only preceded the Intendant two or three hours, during which she could only see me for a moment, notwithstanding any intercession she could make for that purpose; and even then only in the presence of a serjeant and four soldiers of the garrison, who attended her like her shadow. She had a number of particulars to relate to me respecting the journey she had just made in her country, but it was impossible for her to impart them to me, and I could draw nothing from her except sighs and tears, which she poured forth in abundance; after which her escort dragged her away against her will, for the poor creature would have taken it as a great favour if they had detained her as a prisoner along with myself. I was affected by her visit much more deeply than I had been hitherto, and I should have wished very much not to have seen her; yet, when the Intendant arrived, she besought him with so much determination, that he was compelled to yield to her importunity; so much so that he not only permitted her to see me, but even to remain with me, and that too in a place a little less dreadful than that in which I had been, which they made me leave at once: but I believe that this change, so unexpected and so agreeable for me that I regarded it as an interposition of heaven, was rather the effect of necessity than the result of any kind disposition they might have felt towards me. I seemed to have entered another world when I found myself in her society, and out of that detestable place. All my unhappiness now was for my poor wife, who every moment expected her accouchement; she would willingly have been a captive for my sake, courageously despising all the inconveniencies which she would meet with in a place where she would have nothing but solitude; this was one great cause of sorrow -- although this was not the first time that by divine permission she was placed in a similar position, only more inconvenient: in fact, you know that two years ago her accouchement took place in the prison of Sedan, having dragged her from her bed, (which from illness she had not left for six months) to bring her there; by the goodness of God she has again, at the end of three weeks, notwithstanding all these miseries and calamities, brought into the world a fine boy, by which means the number of your brothers is again augmented. However, after being in prison seven months, they thought themselves obliged to bring forward my trial, and for that purpose, on the last of January, the police of Soissons brought me to the prison of Laon, to which place the Intendant arranged that the witnesses with the President should go; and with all these forms it was on the 27th of March that, having confronted me with the witnesses, who had not much to say against me, and having been kept before the bar for more than two hours, to render an account of my faith and of that of which I was accused, and particularly your flight, which they positively wished me to remedy by your return, although I had always borne witness that it was not in my power to do so; they showed an order of council which commanded the Intendant to treat me with all the rigour of the law. -- God gave me grace to reply to all their questions according to the promptings of my conscience, and boldly to confess the truth that we had at one time so feebly defended: but it has now pleased Him to show His strength in my weakness, for in myself and in my flesh I recognise nothing but weakness. However, it was ordered, in expiation of my pretended crimes, that I was still to remain in prison for six months; a judgment which they considered very favourable, and which I attribute to prayer to God on that and on ordinary occasions. I am much indebted to Mons. and Madlle de Lussi who were most kind to me, and whom I shall remember with gratitude all my life. At present I haw mow license for writing than ever. May it please God to preserve us to the end of this persecution to shield us from the storm and the tempest, and to conduct us by His goodness to the haven of salvation."

|

| GOURLENCOUR Situated near Laon, in Picardy, the seat of the Viscomte De Laval. |

The Huguenot token represented in the engraving (full size) was brought from France by the Viscomte De Laval; it is of hard wood, and has much the size and appearance of a chessman The mouldings of the head, however, are so delicately delineated by the lathe, as to give, when opposed to the light, an accurate contour of the classic features of Louis XIV. Tokens of this kind were used by the Protestants of France as symbols of recognition; whence probably those commemorative of Napoleon I. had their origin.

|

| HUGUENOT TOKEN. |

[n] From Portarlington. He served throughout the wars of Queen Anne. He married in France the daughter of Colonel Paravicini, by whom he had seven sons and three daughters, but fearing a lettre de cachet would place the latter in a convent, he sent them to their relatives in Portarlington.

[o] This brother was only in his fourteenth year.

The above article is reproduced from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. 3, 1855.

No comments:

Post a Comment