The Huguenot Colony of Portarlington

(Concluded)

By Sir Erasmus D. Borrowes, Bart.

The domestic accounts of the refugees, though not so ponderous as the "Household Books" of the Northumberlands and Derbys, exhibit the local prices of the day, and prove that "Anthoine Seigne, marchant habitant de Portarlington," was making a strenuous effort to master the troublesome language of his adopted country. "Juillet, 1724. Mr. Le Major C---------, pour balance de tout conte, 8. 8. 1. pr 18 verges de tep (tape) 6d. pr savon 8lb 2. 4. pr 6lb chandell 1. 9. pr une quarte sable (for blotting) 1d. pr 3 estoue de fer à Thompson, smith de Lea 8. 6. pr 4 gallons 3 quartes vinaigre a 1. 8. galon 7. 11. pr une lb ½ houblon 2. 6. pr 3 Stons de fer livré au dt Smith de Lea 8. 6. pr cloux et une paire Inges 4d. pr 3 verges jaratieres 3d. pr 4 on corins et une quarte sable 3d. pr 4 bougles de sangle 2d. pr une lb sucre bostard 9d. au bleu boy pr 1lb savon 3½d, a Monr le Major contant un Moydor 1. 9. 10. au valet 1lb Rolle Tobac 1. 2. pr un sledge ou grand marteau 4. 4. au valet 2 brouss de souliers 6d." Catherine Buliod commences her bill, "Meleidey (My Lady) doit," &c. Another variation is thus given:-- "Maylidy Gennes (My Lady Jane) to John Dupuy Dr." In 1730, we find the French agent of the pensioned officers furnishing his account in French and English indiscriminately, thus:-- "For his letter and certificate 2d, interest 7 pour et. au 3 Octobre 1730," &c.; and a gallant major, in noticing the stock on his farm, refers to his "heaffer calph, and boulgier calph." It is difficult to imagine how the domestic economy of any locality could have been more conveniently adapted to the wants of the noble proprietors of the lost seigneuries than the neighbourhood of Portarlington. For instance, we find a refugee from Saintonge holding 68 acres for £11 a-year; 21 acres for £2 12s.; 11 acres for £2 4s.; and 19 acres for £2 12s. These were the lands on which the beautiful wood, spire, and railway station-house now form such conspicuous ornaments. We have before us a long roll of the names of the French tenants of this gallant officer; and if he let his lands in Saintonge on the easy terms by which his Irish tenant, John Hillen, enjoyed his holding, his dependents could not but lament the change consequent on the sad rupture. For a house, garden, and upwards of two acres, John Hillen paid 5s. a year by labour at 5d. a-day, according to "the tally-book."

Vast quantities of beer were made by the French, even by the lower orders, and this they used at breakfast. We find the refugees of the Bordeaux district availing themselves largely also of the prized beverage of their own native land. In 1726, Monsieur Pennetes, a French wine-merchant in Dublin, furnished a Portarlington colonist with "three gallons of Frontignac wine at 6s. per gallon; a hogshead of clarate, prise agreed, £11; a dousen of wine, 11s.: 29th May, 1729, a oxhead of clarate £12. Same day a oxhead of Bennecarlo at half-a-crown per gallon, allowing 64 gallons coms to £8. Same day I took a hoxhead of Monsieur Terson's wine from Monsieur Pennete's seller, but I gave credit to Monsieur Terson. Une demy barrique de selle de France 6. Le Sr. Pennetes in a surchargé la barrique de Bennecarlo de vingt sh: je lui ay alloné en consideration de long payment, mais ay dessin de ne prendre plus de vin de lui." At a later period we find the inhabitants of Portarlington well supplied with wine, &c. Samuel Beauchamp, of that town (son of Monsieur Samuel Beauchamp, "cy devant avocat au parliament de Paris," who had been imprisoned in France), had his vaults furnished with claret, mountain, canary, white Lisbon, palm sack, and shrub; nor was the celebrated Lafitte unknown there. Later still, in 1757, Joshua Pilot (a retired paymaster and surgeon from Battereau's regiment and the campaign of '45, whose family had felt the fury of the Intendant Maraillac, the scourge of Poitou, imported large quantities of wine to Portarlington direct from the eminent house of Messrs. Barton & Co., of Bordeaux, now of universal fame.i A few more instances may show how well a singularly low price suited the plundered purses of the colonists. Early in the last century we find malt 8s. a brl.; hops, 1s. 6d. a pound; potatoes, 4s. 6d. for 24 stone; bere, 4. 6. a bl.; poultry, 3d. a pair; butter, 2½d. a pound; a kish of turf, l½d.; beef and mutton, l½d. a pound; a milch cow, £1 15s.; a horse, £2 2s., &c.

The French brought with them various trades. The manufacture of linen was carried on upon a small scale by the Fouberts. Of this family was Major Henry Poubert, aide-de-camp to William III.; probably the same Foubert who, seeing Schomberg attempting the passage of the Boyne without his armour, warned the veteran marshal not to omit that precaution. Numerous individuals are described as "marchands;" others to whose names are appended "facturier en laine, drapier, boucher, boulanger, mareschal, marchant gantier, cordonnier, jardinier, macon, maistre charpentier, serviteur deuil, maistre chirurgien, me. tailleur, me. d'ecole, tisserant, serrurier. One French lady was in the habit of importing from France bales of cambric to a considerable amount, forwarded by a relative in her native land. These she disposed of wholesale in Dublin and Portarlington; and a gallant chevalier, who had not yet fled, still dwelling on his estate at Cognac, endeavours to aid his fugitive wife and family in Holland, afterwards settled in Portarlington, by conveying to them stealthily the far-famed brandy of that district, and other merchandise.

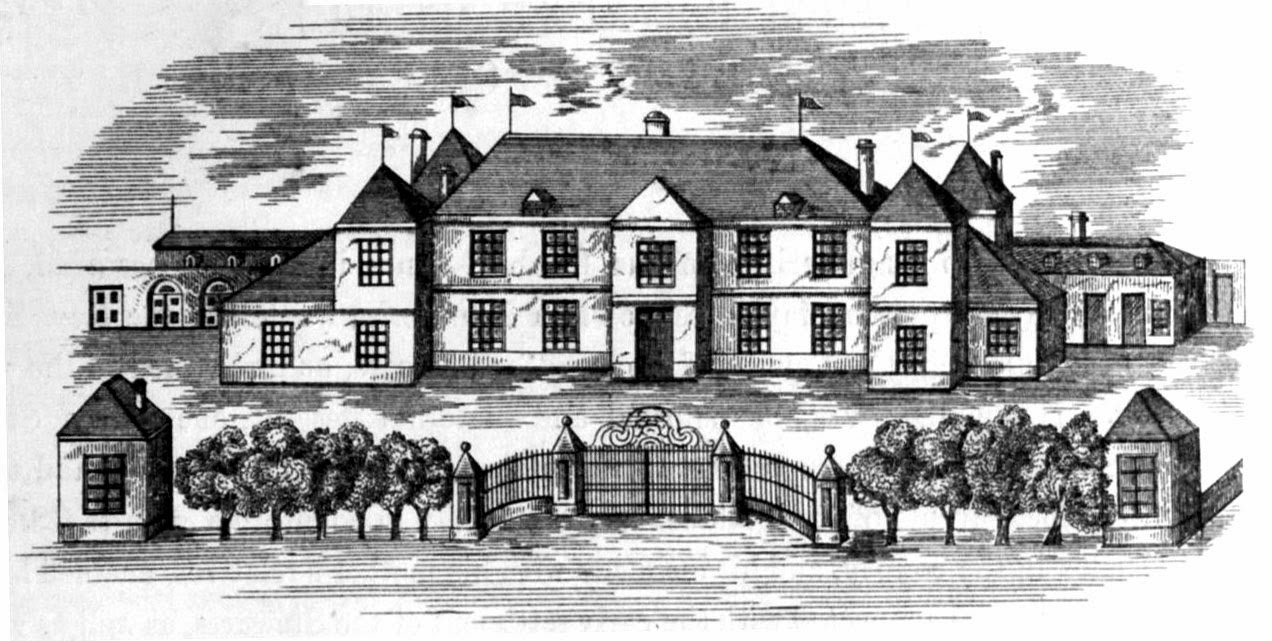

The local names of La Bergerie, La Manche, and St. Germains are significant of their owners' native country; while "the "Welsh Islands" refer us to the "Hollow Sword Blade" or "Welsh Company," from the sword manufacture having been carried on in "Wales. And in the name of "King Street," if not to immortalise, they hoped to honour, the memory of their royal friend and protector.

The schools were the great attraction of Portarlington, the life-blood of the town, and the source of its fame throughout the last century. These took their tone from the high class of French colonists who founded them; and the association of the pupils with such a class, together with the instruction at these seminaries, was calculated to impart a knowledge of the French language in all its purity and perfection; obviating the necessity of a foreign education at a time when intercourse with Europe was a matter of difficulty and delay; imparting an improved and fashionable education to the youth of all parts of Ireland, and inducing many of the Irish gentry to reside there.

Monsieur Le Fevre is said to have been the first schoolmaster in the town. He was the friend and correspondent of Dr. Henry Maude, Bishop of Meath, and founder of the Charter Schools. He was the father of "the poor sick lieutenant," whose lamentable and forlorn condition at the country inn, with his little son, excited the sympathy of the kind landlord and all his family, roused from their inmost recesses the compassionate feelings of "my Uncle Toby," and hurried the gallant captain, in the fulness of his heart, into that breach of a divine command, the remembrance and oblivion of whose offence by the recording angel, Sterne has so beautifully described.

The Register contains the following record: "Sepulture du Dimanche 23e Mars 1717-18. Le Samedy 22e du present mois entre minuit et une heure, est mort en la foy du Seigneur et dans Pespérance de la glorieuse resurrection, Monsieur -- Favre, Lieutenant à la pention. Dont l'ame estant allée a Dieu, son corps a eté enterré par Monsieur De Bonneval, ministre de cette Eglise, dans le cemitiere de ce lieu. A. Ligonier Bonneval. min. Louis Buliod."

To our former notice of the family of Le Fevre, we would add the remark of Monsieur Louis De Marolles respecting his fellow-prisoner in the gallies:-- "I confess to you that Monsieur Le Fevre is an excellent man; he writes like a complete divine; and that which is most to be esteemed is, that he practises what he writes. May the Lord bless, preserve, and strengthen both you and him, and this will afford me singular consolation."

From the first settlement of the French, schools were established by Le Fevre, Cassel, Buliod, Durand, &c. A classical education at this early period could only be acquired in Dublin. From a school bill from Mr. John Spunner, of Dublin, now before us, and dated 1726, it appears that his pupil, aged twelve years, had to ride from Portarlington to Dublin (about forty-five miles); and, instead of the price of the classics, we find such items as these:-- "To the smith, 2s. 8d.; a girth for his saddle, 10d." Prior to the middle of the last century, a school for juveniles was established in Portarlington by Mademoiselle Lalande. This seminary was eminent in its way, and originated others of a higher order, and more varied qualifications. Mlle. Lalande was an educated lady, with a fund of shrewd worldly knowledge, and, as appears from her entertaining letters, a most agreeable correspondent. In one of her school bills of the middle of the last century, we can discover the seeds of that taste for the drama, which distinguished the character of the subsequent age, and attained such maturity in the successful theatricals of the Sheridans, the Le Fanus, the Marlays, Whytes, &c., and ultimately at Kilkenny. The item runs thus:-- "To ye Assembly as Page of Honour to his Majesty, 1s. 1d. To a pair of white shoes for the procession, 3s. 3d." The grandfather of the boy to whom these entries refer, had been an officer in La Mellioniere's corps at "The Boyne;" his father, born in Ireland, had been Dean of Clonmacnoise, and held several ecclesiastical benefices.

Though the lad himself was thoroughly Irish, by parentage and education, we find in the following item a natural and interesting clinging to that language in which his forefathers worshipped, and gave hold utterance to those religious principles which they so nobly maintained. The entry is short, yet significant -- "To a French Psalm book and Prayer do., 5s. 2½d." These books, however, were in general use at all the schools, at which the morning and evening prayers were read in the French language, down to the commencement of the present century. In a printed document, of 1801, relating to the repairing of the French church, the following passage occurs:-- "King William knew from experience, as well as the schoolmasters and mistresses of Portarlington, that attending Divine service in French was the best method to learn it, or preserve it when learned. Though a Dutchman, he attended regularly the French churches in Holland. It was before him and his court that the famous Saurin preached his sermons. About a hundred children leave our school every year. Whenever the celebration of Divine service is abolished by the ruin of our French church, those hundred children will be as many messengers, who will carry the news everywhere. People will imagine that French is a dead tongue among us, and our town might be ruined before we are aware of it. To prevent such a misfortune, let us rebuild both our churches according to the intention of their great founder, King William; who, for fear of any future innovation, had those foundations confirmed by both Irish and English legislatures."j Throughout the last century, the following individuals may be enumerated as principals of schools Le Fevre, Cassel, Macarel, Bonafou, La Cam, Hood, Baggs, Willis, Halpin, Lyons; and ladies' schools, by Mrs. Dunne, Dennison, Despard, &c. Besides the usual grammatical instruction, a simple method was adopted for enforcing French conversation exclusively; and though not altogether just in principle, the end was attained with admirable success. To each class was given an old key, which was passed by one boy to another whenever careful espionage and a sharp ear, with the creeping, crouching approach of the setter, could detect the sound of the proscribed English language. "Anglois prenez la clef," sounded like a thunder clap to the astonished offender; he took the key, which was probably called for that day by the master, and the boy in whose possession it was found was punished. The statute of Henry the 8th proscribing the native Irish tongue was inoperative compared to the vigorous and successful action of this English Language Abolition Act of Portarlington. Miss Lalande was succeeded by the two Misses Towers -- one of whom married Mr. Hood. This school kept by Hood -- who was succeeded by his principal assistant, Mr. Thomas Willis -- became remarkable as the seminary in which some of the most distinguished men of the day -- eminent in rank, in literature, and political attainments -- acquired that earlier teaching which in after-life imparted such brilliancy to their names. Among these may be mentioned, the late Marquis of Wellesley, and his brother the Earl of Mornington, the Marquis of Westmeath, the Right Honourable John Wilson Croker, Chief Justice Busshe, Judge Jackson, Sir Henry Ellis, principal librarian of the British Museum, Daniel Webb Webber, father of the Kildare-street Club, and a host of others, in after-life well-known country gentlemen.

Mr. Willis has left us some anecdotes of Hood's distinguished pupils: he says in his manuscript -- "Lord Mornington's eldest son (Lord Wellesley) I can justly say excelled in everything. Ladies and gentlemen were in the habit of attending our evening prayers and psalms, which were performed with great solemnity on these occasions Lord Wellesley was always chosen chaplain, being the best calculated for that duty: he was also one of the best teachers I have seen, under whose care Mrs. Hood (when called away in cases of emergency) often placed her class, which she might confidently do, as he was more exact than herself in making the boys study their lessons. He acquired such pleasure and delight in teaching, he has sometimes told me, that when a man he would go indeed as schoolmaster. At times he sat as judge, when any of the servants committed a fault, and with due solemnity, dressed in regular form, wearing Mr. Hood's fullbottomed grey wig, examined the witnesses, and pronounced sentence accordingly. He acted the part of King Solomon in a little French Scriptural dramatic piece, taken from Kings, I. chap. 3, in which he displayed the solidity of his wisdom in judging between the two harlots." Mr. Willis details at considerable length, the traits which distinguished the character of the noble Marquis when very young, and states that with those already referred to, he combined all the natural playfulness of boyhood. About the year 1780, when the Irish Volunteers were embodied, the boys got a uniform, and became an expert regiment of juveniles, having a regular sergeant, fife, and drum. This system of military drill became general at all the schools in Portarlington. "A very distinguished corps, admired by officers of regiments passing through the town" was raised at Mr. Willis's school: of this juvenile' force, John Wilson Croker was --

"The stout, tall captain, whose superior size.

The minor heroes view'd with envious eyes."

He is described as a martinet, most expert at drilling with the wooden musket, and an able commander of his youthful company. Many of the earlier pupils of Hood's day attributed, in a great measure, their military success in '98, when called on as country gentlemen to assist in quelling the rebellion, to the mock campaigns in the play ground and the sham lights, in which they were veterans while yet boys.

Others of distinguished name when age had shed its snows on the heads of the once-youthful Volunteers of 1782, would sometimes fondly visit the scenes of their boyish campaigns. The Earl of Mornington and Daniel Webb Webber, were distinguished for this amiable feeling, in which they often indulged. A visit to the old play-ground, and the vivid retrospect we there enjoy, has a wonderful charm in our declining days.

"Viewing it, we seem almost t' obtain

Our innocent, sweet, simple years again;

This fond attachment to the well-known place,

Whence first we started into life's long race,

Maintains its hold with such unfailing sway,

We feel it, ev'n in age, and at our latest day."

At this period there were upwards of 500 children at these schools; the rebellion, however, caused great numbers to be sent home under escorts, who were then sent to English schools: subsequently the schools suffered from the substitution of the English language for French, in the performance of the services of the church -- originally built for the use of the Huguenots. Of late, however, they have again attained a considerable celebrity, and are most creditable to those gentlemen who have revived their former fame.

Several books which belonged to the first colonists still remain, a few of which are as follow:-- Paraphrase, or Brief Explication of the Catechism: by Francois Bourgoing, minister; printed at Lyons by Jaaucs Faure, 1564. This book is bound in vellum, and contains the owner's name, "Estienne Mazick." A Bible, printed in 1652. This book has lost its cover; from long and constant use the gilt edging is scarcely traceable -- each page is separate, yet not one has been lost. New Testament and Psalms in verse; printed at Amsterdam, in 1797. This book belonged to Colonel Isaac Hamon, to whose family allusion has been made. The Psalms in verse, set to music, with various prayers. This was the property of Mademoiselle De Champlorier, previously referred to. A small book, very old, in a vellum cover, containing prayers for the Communion; with others, too many to enumerate.

Significant allusion is made by one of our foreign colonists to the loss of horses, and to money paid "for watching the horses at night." The daring exploits of the notorious horse-stealer, Cahir-na-goppul (Charles of the Horses), had evidently raised the fears of our worthy settlers for the safety of their studs. This French officer loved the chase; he had his "hunting saddles," and had paid " Martin Neef, ye horsfarrier of Kildare, three guynies for curing Tipler." Cahir-na-goppul was an offshoot of the great family of O'Dempsey; through the misfortunes of his renowned race, he had degenerated into a rapparee, and horse-stealer of wide-spread notoriety, carrying his depredations even so far north as Monaghan, by which county he had been "presented," and was hanged at Maryborough, about the year 1735. Even at the present day, the old grand-dame in her cabin terrifies into submission the unruly peasant brat by the dread name of Cahir-na-goppul.

Having requested an aged inhabitant of Portarlington, now in humble circumstances -- a venerable relic of the town, whose day had dawned ere France was wholly extinct -- whose ancestor had been a lieutenant in William's army, and had received half-a-crown a-day as a pension -- to write a short sketch of the family tradition which had been transmitted to her, we just saved from utter oblivion this lingering memorial of the ordeal of other days, with which we conclude our sketch.

We give her own words:-- "My great grandmother's name was La Motte Grandore; her family was so persecuted, that she was sent to Holland with the Cassels, when she was only seventeen years old. A young girl, her cousin, who was steadfast to her faith, they tied by the heels to a cart, and drew on the horse through the street until her brains were dashed out; a young man she was to be married to went after the cart imploring them to stop. Also many of her family (the La Bordes) suffered much; some imprisoned, some losing all they had possessed. My great grandfather made his escape out of prison, where he had been some time, and fled to Holland quite young. He contrived to let his parents know where he was, after great privations; went through the greatest hardships; often had to hide in fields, afraid to enter their own houses. My great grandfather's escape out of prison was most miraculous; they were often hungry, whilst they dare not go to their home to get food, where they had plenty. Memory fails me to let you know the very many stories my poor father used to tell us. His mother was one of the La Bordes. Her father became a soldier when he got to Holland. There he met the Cassels and the young woman (previously mentioned) that her parents sent with them, Lucy La Motte Grandore. Her family were very rich; had good possessions in Languedoc. It is said their place was a paradise; all was comfort. She came over with her husband, John Laborde, who entered King William's army, and was at the battle of the Boyne, quite near Duke Schomberg when he was shot." This respected descendant of these gallant Huguenots closed her interesting tale with an expression of regret that the infirmities of age, and the loss of her contemporary relatives, should render it so imperfect.

The register contains the following record confirming the statement of our aged informant: "Du Dimanche 26 Xbre 1703. Le Jeudy 16 dernier vers les 5 heurs du matin est né un garçon a Jean La Borde et à Anne Graindor sa femme, lequel a esté baptisé cejourdhui par Monsieur de Bonneval min. de cette eglise. Parraine le d' Jean La Borde. Marraine la d. Graindor, ses père et mère; et nom lui a esté imposé Jean. Jean La Borde. Anne Graindor. Bastagnet, ancien. Proissy d'Eppe, ancien. Guion, ancien. A. Bonneval, min." The register also contains an entry of the baptism of her father, Abel Cassel, "aux prières du soir." 12th August, 1736, which states him to be the son of Isaac Cassel and Anne La Borde; and another of the same family is baptized "aux prières du matin." This shows the practice of two daily services.

The French registers of Portarlington are replete with genealogical and topographical information. Dowdall's map of the town -- remaining among the records in the Custom-house, Dublin -- describes the houses and plots of the early colonists; and the Book of Sales, at Chichester-house, in 1703, in the Dublin Society's library, is still more full on these topics. The Journals of the Irish House of Commons also afford much information regarding military rank and pensions. But, with the extinction of the French inhabitants, the interesting family papers, the lively and romantic journal, and the faithful and stirring tradition have also with one exception passed away, and we are just by one generation too late to reap the rich harvest of Huguenot history we might otherwise have secured.

[i] The quantity of wine consumed in Ireland at this period must have been enormous, as shown by the contents of Lord Conway's cellars at Lisburn, which were to be sold on his death, as advertised in "Pue's Occurrences " in 1731 -- viz.:-- "19 hogsheads of claret of the great growth of Lafitte; 12 hogsheads of Margeaus; 29 do. of the great growth of Lafitte. and old; 7 do. of choice Graves claret; 8 do. of French white wine; also, a parcel of four-year old brandy." The white wines are stated to be "the best Priniaque." At this sale was also to be disposed of "a fine armoury, consisting of carbines, pistols, broad-swords, buff belts, and kettle-drums," memorials of the civil wars of Charles I., and the good services done by the Lisburn garrison and the regiment of horse commanded by Edward, Viscount Conway.

[j] A poem of the early part of last century in terms somewhat satirical, thus alludes to the great Captain of the Portarlington colonists:--

"JOSHUA might still ha' staid on Jordan's shore--

Must he, as William did, the Boyne, pass o'er.

Almighty power was forced to interpose,

And frighted both the water and his foes:

But, had my William been to pass that stream,

God needed not to part the waves for him.

Nor forty thousand Canaanites could stand;

In spite of waves and Canaanites he'd land.

Such streams ne'er stemm'd his tide of victory;

No not the stream ! -- no, nor the enemy?"

And in figurative language, the poet anticipates by ages a modem invention of world-wide utility --

"What glories are for Nassau's arms decreed,

His own steel pen shall write, and ages read "

The above article is reproduced from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology, vol. 6, 1858.