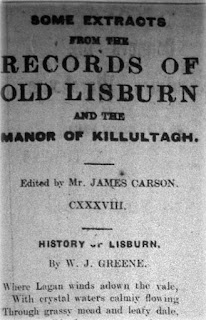

FROM THE

RECORDS OF

OLD LISBURN

AND THE

MANOR OF KILLULTAGH.

-- -- -- --

Edited by JAMES CARSON.

-- -- -- --

CXXXVIII.

-- -- -- --

HISTORY OF LISBURN.

By W. J. GREENE.

With crystal waters calmly flowing

Through grassy mead and leafy dale,

With wild flowers sweet in beauty blowing.

Here Lisnagarvey takes her seat,

With sturdy sons and lovely daughters,

The river twining round her feet

Reflect her beauty in its waters.

Lisburn or Lisnagarvey, by many esteemed the handsomest inland town in Ireland, is situate eight miles south of Belfast and one hundred north of Dublin, on the River Lagan, which divides the Counties of Antrim and Down. The town is a very old one, being anciently one of the fastnesses of Hugh MacNeil Oge, son of Neil Oge O'Neil, one of the Princes of Tirowen.

Before the reign of Queen Elizabeth, Lisburn (then called Lisnagarvagh) was a small village, and is said to have taken its name from Lis-na-garvoch, the fort of the gamester, a circular rath situated on the hill on the north side of Wallace Park.

It is similar to several others in the neighbourhood, and seems to have been enclosed with deep ditches, which may have been enclosed with strong palisades, a very high and thick rampart of earth and timber, and well flanked with bulwarks. There is also one on the White Mountain, another at Todd's Grove, and another on the Clogher Hills, near Plantation, in the Co. Down. It is generally believed they are the remains of the strongholds and dwelling-places of ancient Celtic Chieftains, and were so placed that signals by fire could be easily seen from one to the other. They seem to have been in use up til the year 1600 from a description of the stronghold of O'Neill, the Fort of Ennisloughlin, between Moira and Lough Neagh, in 1602. The prevailing religion was Druidic, before the introduction of Christianity by St. Patrick A.D. 432 till A.D. 465. A cromlech, supposed to be the altar on which were offered human sacrifices, is still to be seen at Giant's Ring, Ballylesson, Co. Down.

The occupations of the people of Ireland generally seem to have been mainly agricultural and the rearing of cattle, when they were not fighting, which, as it appears from history, they were hardly ever free from, between some of the different septs or clans of Celt, Saxon, and Norman, who have fought at different times for possession of the country or parts of it. The weaving of linen and serge was also carried on from a very early age, the principal seats of industry being Ard Macha (Armagh), Bally-Lis, Nevan (Newtownards), and Beann-Char (Bangor).

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth a very unsatisfactory state of feeling existed between the Government and the native Princes of Ulster. In those days the dynasty of the O'Neills was very powerful and no less popular throughout the northern province. Having, after several years' fighting, failed to conquer these island chieftains, the Queen tried to win them over by conciliation. An offer of an earldom was made to Shane O'Neill, but the proud chief would not accept any such favour at Her Majesty's hand. He replied that by blood and birth his rank placed him far above the peerage. "My ancestors were kings in Ulster," added the O'Neill; "they gained their power by the sword, and I shall uphold my rights by the same weapon." In the autumn of 1585 Sir Henry Sidney, the Queen's Irish Deputy, made the tour of Ulster, accompanied by an armed bodyguard of mounted soldiers, and during his journey called on the leading princes of the North. He was anxious to pay marked court to the Captain of Killultagh, one of the most popular and influential of that powerful Sept; he was the owner of a very large territory and lord of three castles, each of which was encompassed by a fort of great strength -- Ennisloughlin, near Moira; Portmore, on the borders of Lough Neagh; and the third stood on a mound that rose above the River Lagan and close to the tiny village of Lisnagarvey. The forts of that castle overlooked the entrance from the County Down side of the water, and in case of invasion was well situated for protecting the chief from every intrusion of his enemies by that route.

The Captain of Killultagh.

Who looked upon the English as the "invaders of his country," did not receive the Lord Deputy with that cordial hospitality which is the traditional character of his countrymen. It is said he felt insulted by Sir Henry's mode of introducing himself, who sat on his horse outside the rampart while he sent one of the officers of his guard to announce to the Captain that the Irish Lord Deputy was outside and desired to speak with him. He indignantly refused to cross the doorway of his castle, and said, "If the English Deputy wishes to pay his respect to me I will be happy to see him inside these walls." Indignant at the reception accorded him by the Irish chieftain, Sir Henry turned away in anger from his gates and thus expressed his feelings in his report to the English Cabinet: "I came to Killultagh, which I found ryche and plentyfulle after ye manner of those countryes, but ye Captain was proude and insolent; he would not leave his castle to see me, nor had I apt reason to vysyte him as I would. He shall be paid for this before long. I will not remain long in his debt." The Queen, on hearing of the cool contempt with which O'Neill treated her Deputy became more determined to subdue the Irish Chieftains, and three famous commanders were sent over to Ireland to put down, at any cost of men and money, the princely power of the O'Neills and that of all the other chiefs.

In 1587 such overtures were made in favour of peace to the heads of clans and offers of full pardon that Brian M'Art O'Neill and his father, the Captain of Killultagh, pledged themselves and their vassals, or tenants, that they would submit to English rule. Sir John Perrott accepted the promise in the name of Her Majesty; but when Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tirowen, once again rose against the Queen, the Captain and his son forgot their promise, and joined their kinsman's army. In 1602 an expedition under Lord Mountjoy was sent against them, who captured their Fort of Ennisloughlin, and after the most terrible sufferings endured by the adherents of O'Neill, who were compelled to seek subsistence by devouring one another, the rebellion ended by the humble submission of O'Neill to the officers of the Queen. The Lord Deputy, on the Queen's part, promised a full pardon to him and all his followers, with a new patent for his lands, except certain portions reserved for chieftains received into favour and for the use of English garrisons. At the meeting of the Council in Dublin at which O'Neill attended after his submission, where he was received according to the rank of his English title; the announcement was made of the death of Queen Elizabeth, when O'Neill was observed to suddenly burst into tears. The Irish Chieftain said he was unable to contain his grief at the loss of a mistress whose moderation and clemency had at length caused him to regard as a generous benefactress; but his enemies said that he was mortified at his own hasty submission and that he regretted that he had not held out a few days longer, when he might have benefited by the change, at least make better terms. Be that as it may, with the passing of Queen Elizabeth passed away the independence and power of the O'Neills, Earls of Tirowen, Captains of Killultagh, and the Lords of Lisnagarvagh.

In the year 1604, Conn O'Neill in consideration of a pardon granted to him by King James the First, at the suit of Sir James Hamilton, consented that these lands, with others, should be granted to him by letters patent. From Sir James Hamilton they passed about the year 1609 by letters patent to Sir Fulke Conway, of Conway Castle, in Wales, one of the three officers, selected by Queen Elizabeth to carry on the war against the native princes, under the command of the Earl of Essex. The other officers were Colonel Arthur Chichester and Lieutenant-Colonel Hill, from whom the Earl of Hillsboro' family are descended.

Under Sir Fulke Conway's ownership the village of Lisnagarvey was very much improved, the streets laid out in their present form, Castle Street, Bow Street, Market Square, and Bridge Street, and the Sir Fulke and his successors gave great encouragement to English and Welsh tenants to come over and settle here, which a great number did.

In 1623

In the reign of James the First, the Church, or Cathedral as it is now generally named, was opened for the use of Divine Service, it was then called the Church of St. Thomas, afterwards altered to Christ Church in 1662, and raised to the dignity of a Cathedral for the united diocese of Down and Connor by Royal Charter of Charles the Second, to reward the fidelity of the inhabitants of Lisburn to his father and himself.

Sir Fulke Conway died without issue in 1627, when his brother, Mr. Edward Conway, succeeded to the estates. Early in the reign of Charles the First he was presented with the lands of Derrievolgie, in addition to the estates which he obtained through his predecessor, and in a short time afterwards he was raised to the peerage.

About the year 1627 Lord Conway commenced to erect a castle on a picturesque hill commanding a beautiful view of the valley of the Lagan. A portion of the wall which formed the entrance is still standing on the south and east side of the public walks called the Castle Gardens. In a book of travels in Ireland, published by an English gentleman in 1636, the author says:-- "From Belfast to Linsley Garvin is about seven miles, and appears a paradise compared with any part of Scotland. Linsley Garvin is well seated, but neither the towne nor the country there about is well planted, being almost woods and moors until you come to Drommore. The town belongs to my Lord Conway, who hath there a hainsome Castle, but far short of Lord Chichester's houses. Lord Conway's garden and orchard are planted on the side of the hill on which his house is seated, at the bottom of which hill runneth a pleasant river, the Lagan, which abounds in salmon."

The castle became the head of the manor. The grant of King Charles also conferred the privilege of court's leet and baron, viw of frank pledge, manorial courts for debts not exceeding two pounds sterling, a court of record every three weeks for sums not exceeding £10, a weekly market and two annual fairs, which, as our readers are aware, remain is existence till the present day.

(To be continued.)

(This article was originally published in the Lisburn Standard on 20 June 1919 as part of a series which ran in that paper each week for several years. The text along with other extracts can be found on my website Eddies Extracts.)

No comments:

Post a Comment